Breathing

16 December 2021

No one needs to be told how to breathe. It’s automatic. What I didn’t know before a week or two ago, however, is that humans are one of very few creatures who can override our automatic breathing and control it consciously. I don’t know why this is so and if anyone else does, it’s not important enough for me to find out. I simply accept it.

The fact that we can consciously override our automatic breathing opens up several possibilities. Our ability to consciously control our breath allows us to sing, to project our voices in theaters or when speaking publicly, use our “Command Voice,” play musical instruments and many other things.

What’s more, breath control has been shown to engage different parts of the brain, enhancing awareness, relaxation and suppressing the “fight/flight/freeze” response. Some units in various branches of the military train “conscious breathing” as an extremely simple but effective way to re-focus during combat operations (https://upliftconnect.com/how-to-stay-calm-like-a-navy-seal/). Those of us who have taken Lamaze classes (I attended with my wife at the time she was pregnant with our daughter) already know how it works. In a different context, I taught my late mother how to do a version of “conscious breathing” to help her settle herself when she would become agitated because of her dementia. It usually worked best when I was there to guide her, but she retained the technique and, God bless and keep her, she used it on her own from time to time.

In a martial arts context, it allows us to concentrate our internal energy – our qi – at the decisive moment. You’ve seen karate and kung fu artists shout as they punch or kick boards in two. In tai chi, we have similar vocalizations – “Ha” and “Hen” – which I will go over in class when the time is right to do so.

Before we get to this point, however, we practice more gentle breathing, and we do it in a few different ways; one for qigong and meditation, and one for tai chi. This post will discuss each.

4-Count or “Box” Breathing

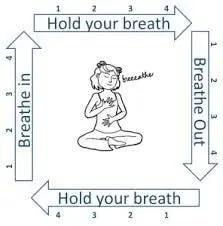

Qigong and meditative breathing is very similar to the “4-count breathing” or “box-breathing” shown in the image above. We breathe in, then “suspend the breath,” breathe out and suspend the breath. This is a conscious action – we “override” our bodies’ natural breathing patterns.

When we do qigong, as a rule (with exceptions), we inhale on the “yin” or preparatory portion of the exercise, suspend the breath, then exhale more-or-less forcefully for the “exertion” part of the exercise. In “Pull Bow, Shoot Hawk” from the “Eight Pieces of Brocade” qigong set, we breathe in during the “gathering in” portion, then breathe out when we “pull the bow.” An exception from “Eight Pieces of Brocade” is “Wise Owl Gazes Left and Right,” where we breathe in to enhance the stretching of the chest muscles. We can further refine our breathing during “Eight Pieces of Brocade” in places like “Bounce on Heels,” by actively breathing in and simply letting our “exhale” be a relaxed release – simply letting the air go, if you will. In any case, the breath is coordinated with the activity.

In meditative breathing, the pattern of in/pause/out/pause is the same, but more mental effort is devoted to an even “cadence” of breathing – counting to 4 is common, as is shown in the image above. The breathing is full, but since we’re not physically doing anything, it’s much more relaxed.

Tai Chi Breathing

Tai chi breathing is different in that no attempt at all is made to coordinate the breathing to the action. We just breathe naturally and normally. There are several reasons for this:

o Each posture and transition in tai chi is intrinsically “yin” (passive/gathering in/yielding/soft) and “yang” (active/issuing out/exerting/hard) at the same time. Which of the two it is depends entirely on “yi” or the “intent” of the player at the instant he or she is performing the movement. I hinted at this on Monday when I showed how the “hook hand” can either be a locking-in movement or a strike, depending on what the player wants it to be. So with few exceptions – the punches and kicks being the most obvious ones – there is no intuitive place to breathe in or breathe out in the form.

o It’s frustrating and pointless to try. We can try to coordinate our breathing to the postures-and-transitions, and most players do try this when starting out. But there’s so much to pay attention to already, even if (perhaps especially if) one has been doing tai chi for a long time – that what ends up happening in actual practice is that we usually give up trying to coordinate our breathing not long after “Single Whip.” Not only this, but trying to coordinate our breathing to the action will invariably have us huffing-and-puffing by the end of the form, which is something every Grandmaster since Yang Banhou has expressly warned against doing. We should be as relaxed at the end of the 108-posture form as we are at the beginning.

Similarities and Cautions

One thing which is common to everything we do is “abdominal breathing.” I refer to it as “filling the lungs from the bottom up.” If you’ve sung in choir or played a wind instrument, you already know how to do this. If not, it’s done by distending the belly (making it bulge out somewhat) and endeavoring to send the air we breathe as deep into our lungs as possible. The Chinese have a saying: A healthy person breathes from his belly; a sick person breathes from his chest, and a dying person breathes from his throat.

Similarly, nothing we do in class should leave us short of breath or breathing harder than we do when we walk. If this is happening, the following are the likeliest causes:

- We’re putting too much energy into our movements. This happens when we take stances that are too wide, taking larger steps than we should, or when we over-extend (as with things like “Press,” “Push” and so on), when we’re not centered and rooted, or if we’ve progressed farther than we’re conditioned for (i.e., doing the kicks in the second section before we’re ready). Back off just a bit until things settle down

- Going too fast or too slow. Tai chi has a natural pace and rhythm, one that’s relaxed and calm. We can do the form fast, and I’ve demonstrated it before. But we shouldn’t do it fast until we’re comfortable doing it slowly, and even then we shouldn’t do it very often – bad habits easily creep in! It’s the same thing when going too slow or holding postures until they feel uncomfortable. We should be able to stay in any posture long enough to take an “internal inventory” of how it feels, but staying there any longer is contrary to the spirit of the art and builds just as many bad habits as going too fast.

- We’re emotionally or mentally distracted. If our minds or hearts are elsewhere, we won’t have the inner calm necessary to get the most out of the exercises. Sometimes focusing on the form helps to center and calm the mind and body. Other times, though, those mental or emotional distractions are just too strong. That’s okay too. We’re all human, and we owe ourselves the compassion and self-forgiveness to admit that sometimes, today is just not the day.

- We’re actually sick. It’s up to each of us whether the benefits of doing tai chi or qigong are worth it when we feel unwell. Sometimes it is, and sometimes it isn’t.

Breathing is as central to tai chi and qigong as it is to everything else. The “conscious breathing” techniques we learn and practice in class have benefits far beyond martial arts – they can positively affect our mental and emotional states, promote better physical health, and enhance our awareness of our surroundings. That’s quite a few benefits, all from doing consciously something we normally do automatically!