The Tai Chi Classics

I have serious students.

This is an incredible gift to any teacher. Students who share the teacher’s passion for the art encourage

the teacher to be better, to teach better, to take their questions, concerns and requirements seriously.

It means they’re an active part of the class, not simply passive, empty vessels.

How lucky I am to have such students!

Tai chi is tailor-made for such serious students, and rewards their hard work and inquiry. The first part

of learning tai chi is the external – knowing where the hands and feet go, memorizing the form, grasping

the Ten Essential Principles. The next phase is exploration of its internal characteristics – how it’s

supposed to feel inside; where qi comes from, where it resides and how it’s cultivated and manipulated;

how to interact with others and so on. The student is exposed to these internal characteristics early on

of course, but it’s not until the first phase is mastered that we can really lay hold of their essence or

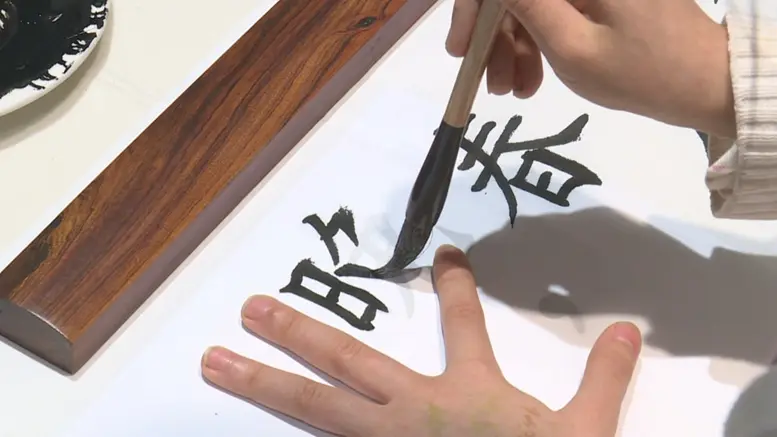

value. To try to grasp the second before mastering the first is like trying to master calligraphy before

learning how to read.

When a student reaches this point, they’re ready to understand what the Grandmasters of the past have

written about the art. Quite a bit has been written about it and we are fortunate that the important

parts have all been translated into English.

The essential texts in tai chi – all family styles – are referred to as the The Tai Chi Classics. (Link: https://thetaichinotebook.com/tai-chi-classics/) This is a collection of short writings and full books written in the 19th and 20th centuries. This link is an excellent resource and I encourage every student to save it and study it. Even if some of the concepts in it seem mysterious, “airy-fairy” or even meaningless, they’re the kinds of things that reveal themselves once we’re ready to grasp them. It’s just like the calligraphy example above – the most beautiful writing in

the world is useless if you can’t make sense of it.

The earliest of the “Tai Chi Classics” are from relatively late in the Qing Dynasty (1644-1910), and are

written in a scholarly, poetic style that benefits from some interpreting in addition to straight

translation. The first thing you need to know is that the link, and the commentaries that are embedded

in the link, use the “Wade-Giles” spelling for Chinese words. I’ve written and spoken before about this –

review this blog post for a quick refresher (https://ewstudios.com/jargon-chi-and-hocus-pocus/). I point this out because with a few exceptions, I tend to use pinyin spellings. For your study, if a word written in Wade-Giles seems unfamiliar, it usually helps to sound it out. This is because Wade-Giles is a phonetic approximation – what a native English speaker hears – whereas pinyin assigns some new “sound values” to letters that don’t correspond to how those same letters sound in English. For example, the word 採 (“Pluck” or “Pull” or “Large Roll-back”) is spelled “Tsai” in Wade-Giles because that’s what it sounds like to English speakers; whereas in pinyin it’s spelled “cai” – the Chinese use the letter c to stand in for the TS sound in English.

The next bit of advice concerns the scholarly style of 19 th century Chinese writing. I could spend the rest

of this essay explaining why the Chinese had two different ways of writing and speaking. For our

purposes it’s enough to know that it’s related to the Imperial civil-service examinations that went back

to the 1300s and went all the way up to 1908, and is similar (though not identical) to the difference

between the poetic language in the Christian Bible, versus the everyday language the pastor uses in his

sermon. For example, the “Tai Chi Classic” attributed to Chang San-feng (pinyin: Zhang Sanfeng) says

the following:

Peng, Lu, Ji, An,

Tsai, Lieh, Zhou, and Kao are equated to the Eight Trigrams.

You’ve seen and heard me talk before about how this is an aid-to-memory, and how “peng-jin”

(“warding off energy”) isn’t exactly like the Bagua trigram that refers simultaneously to “South,”

“Heaven,” “Summer,” “Father” and so on. In the same way, the steps don’t correspond exactly-and-

literally to the Five Elements of Chinese Alchemy. They are simply cultural references meant to connect

tai chi to the world around us.

Of course the authors of the Classics were all Chinese; with the exception of Cheng Man-Ching, none

ever left his native land, and they were every bit as immersed in their own culture as we are in ours. For

this reason, it’s important as a general rule – not merely with the Classics but with everything written in

a foreign language – to distinguish between translation and interpretation. Translation is the “simple”

substitution of a word in one language for the closest meaningful equivalent in another language.

Interpretation, on the other hand, is the more challenging task of determining what an author means

when he or she writes something and it’s been faithfully translated. Every one of us has no doubt run

across this difference when we attempt to make sense of an instruction leaflet that was originally

written in a foreign language and carelessly translated into English. It’s why the task of technical writing

(and writing about tai chi IS “technical”) is best performed by people who are experts on the topic, and

not merely fluent.

Peng is an excellent example of the need for technical fluency in addition to facility with the language. It

may seem hard to believe, but you and I as tai chi players probably understand this word better than a

native Chinese speaker! This is because peng the way we mean it is a jargon-word within tai chi that

does not exist in ordinary conversational Chinese. If you input the character for peng (掤) in Google

Translate, it will return the pronunciation “bing” and translate it as “arrow quiver.” No amount of

mental gymnastics can get you from “arrow quiver” to “Warding-off Energy” and since it’s “tai chi

jargon,” it’s pointless to try. This character means something extremely specific in the context of tai chi;

someone who is fluent in Chinese and English but not a tai chi player won’t have this understanding.

In the case of the Tai Chi Classics, both translation and interpretation are going on at the same time. We

have to read sympathetically; that is, we have to read not only the words as they’re transmitted to us,

but also search for what the original authors really meant. Sometimes they’re speaking in idioms – “Tai

chi is born of Wuji and is the mother of Yin & Yang” is a re-stating of a part of the Tao Te Ching. It means

something in Taoism, but in tai chi it means little without an understanding of “Yin-Yang Theory” as we

discuss it. You might also detect a hint as to why it’s taken me so long to write about this: There’s a

fundamental understanding that’s necessary to even make sense of what you’re reading, and this

understanding can only be taught and felt – it can’t be communicated through reading or watching

videos or just thinking about it hard enough.

The commentary in the link is valuable and worth the time to read, with a caveat, which is this: Like any

commentary on any topic, it is an expression of the author’s opinion. This is not to devalue his opinion –

I don’t hold to the old shopworn saying about what opinions are like and what they’re full of. Some

opinions are worth more than others, and in the case of a real expert, they should be carefully listened

to. But it’s important to differentiate between “expert” and “authority.”

I’ll use an example with which I’m very familiar: in the Masonic fraternity, we go to considerable trouble

to point out to the newly-made Mason that while there are experts on Masonic history, philosophy etc.,

there is no such thing as an authority on Masonry, in the sense that no one man can speak on behalf of

the whole Fraternity. It is up to each Mason to determine what Masonry means to himself. In the same

way, this author presents a valuable insight into what the Classics are and what they mean. But it is up

to each of us to understand, as we read, that he is writing through his lens, based on his unique

experiences and perspective.

The author of the commentaries is without doubt an expert; but the text on which he’s commenting is

authoritative. We therefore need to read his commentary – as well as the source material he translates

– sympathetically, but guided by this understanding.

As to the author’s commentary, I have no meaningful disagreement with him – you can read what he

has to say in confidence. The only things I can add are small and trivial, and my few disagreements are

truly matters of interpretation; e.g., he and I see shen differently, but not enough for me to say he’s

wrong.

We’ll be discussing this material in class – perhaps even before this post goes to print!