Tai Chi Fundamentals – Yin/Yang Theory

Much of what follows comes from notes I took at a seminar with Grandmaster Yang Jun near Detroit in September 2019. It was a transformative experience, not only to receive instruction from the Grandmaster, but also to learn what he thinks is important, and how he teaches it. I tried to learn as much about “tai chi teaching” as I did about “tai chi playing.

It was like taking a drink from a firehose. Yang Jun is my age (at the time of writing I’m 52) and he’s been at the art since age 7 or so. And with the passing last year of his grandfather, Grandmaster Yang Zhenduo, he’s literally IT when it comes to authorities on Yang family Tai Chi.

Yang Jun spent a fair amount of time talking about “Yin/Yang Theory – as well he should. It is the foundation of Tai Chi, and the principle on which everything related to the art is built. It is best expressed in this way:

Yin and Yang can be thought of as Mutually Dependent Opposites

Yin and Yang aren’t things, so much as they’re a representation of things in opposing relationships. For example, hot and cold, up and down, left and right, hard and soft, rough and smooth, and so on. They are also mutually dependent. What this means is there can be no concept of “hot” without the concept of “cold;” no “up” without “down,” no “yes” without “no,” no “this” without “that,” etcetera. This explains why the small white circle is in the black swirl, and the small black circle is in the white one – each quality carries within it the nature of its opposite.

This business of Mutually Dependent Opposites lies at the heart of Taoist philosophy (there is a folk religion related to Taoist philosophy which is beyond the scope of this post and our class), and is in fact as close as Taoism comes to a “Creation Story.” One of the passages of the Tao Te Ching summarizes this “Creation Story” as follows:

Dao gives birth to One

One gives birth to Two

Two gives birth to Three

Three give birth to the ten-thousand things [meaning All Things]

The ten-thousand things carry yin and embrace yang

They mix these energies to enact harmony.

https://www.wussu.com/laotzu/laotzu42.html

How this applies to tai chi – which is a martial art – is that we meet our opponent with an action opposite to his. If he is forceful and solid, we are yielding and nebulous; if he is yielding, we are strong and solid. And if he is still & calm, so are we; but as the “Classics” remind us, “the instant my opponent moves, I am already there.” At the point my opponent and I are in physical contact, ideally, there is a sort of balance between both strong/yielding, solid/nebulous.

This of course takes LOTS OF practice.

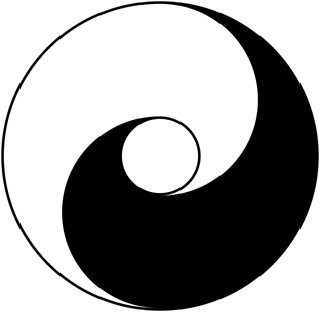

Moving on from what Grandmaster Yang said, I’ll add my own thoughts, the principle of which is that I think one of the older symbols related to tai chi in fact expresses our martial art better.

This is an older symbol and in my mind it communicates the third element – stillness – better than the yin-and-yang symbol we’re all familiar with. It represents the central stillness and balance that should be at the center not only of any encounter (as I alluded to before) but also within us.

The final word on the topic comes from an unlikely source. Hermann Hesse was a German-born author whose most well-known book, “The Glass Bead Game,” was written in self-exile in Switzerland and first published in Austria. There are many elements of Chinese culture “baked in” to the book. It’s quite clear, for example, that the titular game, whose rules are alluded to but never fully spelled out, was inspired by the Chinese board game “weiqi,” known in Korea as “baduk” and in Japan (and the rest of the world) as “Go.” There are many references to Taoist philosophy, without coming right out and saying what they are. The clearest one is a phrase told to the central character from his old mentor, and it’s as good a word-picture of the symbol above as any I’ve ever encountered:

“But never forget what I have told you so often: our mission is to recognize contraries for what they are – first of all as contraries, but then as opposite poles of a unity.”