Attack and Defend Don’t Exist

Scott Rodell (the guy in the blue tangzhuang) is a tai chi player and teacher, and one of the foremost scholars in Chinese swordsmanship anywhere in the world, including China. It’s no exaggeration to say that he’s as responsible as anyone else for returning Chinese sword to its “practical” origins from the visually-dazzling but impractical wushu forms displayed in performances and competitions.

He posted the following passage on Facebook and made it public, so I take the liberty of quoting him verbatim et in toto. It has something to teach us as empty-hand players as well.

Deflections in Chinese Swordsmanship*

~ Scott M. Rodell

Recently, there’s been a reoccurring discussion of how Chinese Swordsmanship purposely deflects with the blade flat. Some today, not being familiar with the principles of the art, but eager to practice, have borrowed edge parrying from European sword work. There are a number of reasons why both Jiànfǎ and Dāofǎ avoid edge on edge parries. These reasons include the Sānméi (three plate) structure of the blade. The high carbon, hard edge plate of Chinese swords make them excellent for cutting and maintaining an edge, but brittle in edge on edge encounters.

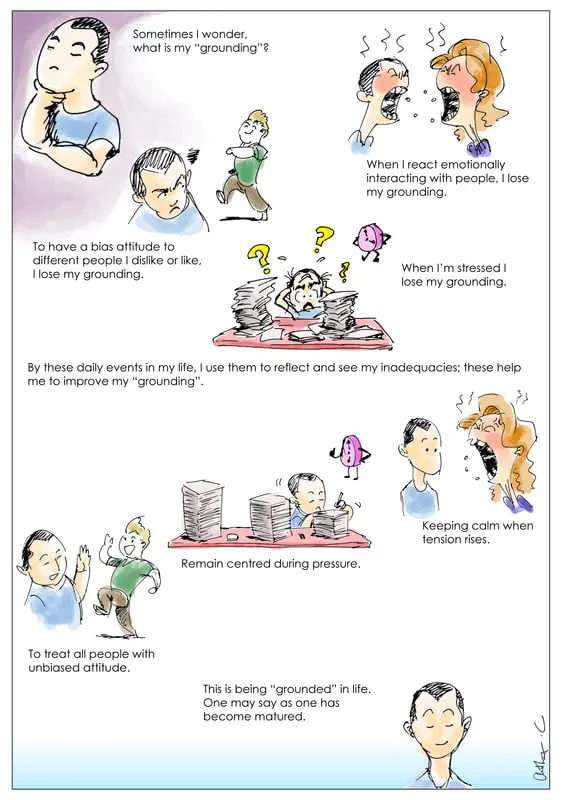

Beyond metallurgical reasons, Chinese sword work deflects with the flat for reasons of principle. The core principle of the Chinese approach to swordplay is that each response to the duifang’s blow is not a dualistic defense then counter with an attack, but is one fluid seamless movement. There is no parry and riposte in either Jianfa or Daofa. There is, what in Mandarin is referred to as dānxíng (單形), literally a single or simple form. The act of deflecting is taking aim flowing into counter-cutting. Properly speaking it is a deflect-cut. One word, one action, no thought of defending then looking for an attack. There is mind intent with the deflection and at the target simultaneously as one larger whole. Attack and defense don’t exist in well-practiced Chinese Swordsmanship. Deflecting with the blade flat not only aligns the counter-cult, being one continuous movement, it also generates power for the cutting action of the deflect-cut movement. Being but one movement, without any hard change in direction, no momentum is lost. The momentum of the deflection thus provides power to the cut it generates. For these reasons, Chinese swordsmanship focuses on only using the blade flat to deflect.

Tai chi is by no means unique in “our defense is also an attack.” The difference is the way we go about it. In Western sabre as well as most “external” martial arts, the idea of a parry or block is to meet the opponent’s blade (or punch or kick) head-on in such a way that our parry is stronger than his blow. Karate treats its powerful blocks as an attack on the opponent’s arms and legs. If the parry or block injures the opponent, so much the better.

This sort of thinking doesn’t exist in tai chi. We work with the direct force the opponent gives us and transform it to our advantage. We yield, neutralize and redirect when he is solid and straightforward, and apply force when he is weak (as in when a blow has expended all its energy) or off-balance. This too is no secret – Jiujitsu, aikido and indeed all grappling arts have this principle. As before, the difference is in the way we go about it.

So it is when we move from the martial to the civil. We tend to find things in our world easier to deal with when we work with them rather than fight them. Carefully “rolling” a sack of wet clothes into our grasp is easier than just hoisting it straight up. Coaxing our pets along is easier than trying to drag them unwilling on their leashes. Figuring out how to get a junior Soldier or subordinate coworker to want to do a task is easier in the long run than just ordering him or her around like a slave-driver. Appreciating the weather as a part of nature is easier than stressing out that it’s raining. Using the right tool for the job – and letting the tool do its job – gets better results than treating everything like either a hammer or a nail.

Tai chi, if we apply its lessons beyond the classroom, ought to shift our thinking over time…

*NB. Jianfa means “straight-blade swordsmanship,” Daofa means “sabre swordsmanship” and duifang means “opponent” but more in the collaborative spirit of friendly game-play than that of life-and-death arch-enemies.